Mental Healthcare Matters – So Why Can’t Some New Yorkers Access It?

In a powerful gesture of recognition, the U.S. House of Representatives designated July as National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month in 2008, paying tribute to Bebe Moore Campbell, a Black American author and journalist. Campbell’s incisive writing explored the intersections of racial discrimination and mental health, highlighting how structural inequality shapes both the development of mental illness and access to mental health care. Though Campbell passed away in 2006, her legacy endures, urging us to confront these persistent disparities.

Unlike May’s National Mental Health Awareness Month, July offers a focused lens on the historical and systemic racism that has deeply affected the mental health of New York’s minority populations. In a borough as diverse as Brooklyn, it is imperative to recognize how race and socioeconomic status intertwine, often leaving the most vulnerable and neglected communities without necessary care.

“You see this very clearly in Brooklyn, where the way some people live and the way others live is just glaringly different,” says Amy Desautels, Program Director at BCS Personalized Recovery Oriented Services (PROS). “We know that beyond poverty, there’s also a color component, where structural racism has kind of worked into every element of society, whether purposefully or through benign neglect. There’s also generational and intergenerational trauma that comes from those things.”

BCS PROS members enjoying drinks and snacks.

Organizations like Brooklyn Community Services (BCS) are at the forefront of addressing these issues, providing crucial mental health support and advocacy. By raising awareness and delivering essential services, BCS is working to bridge the gap and ensure a healthier future for all New Yorkers. Their efforts are particularly important in light of recent findings on mental health disparities in the city.

According to The State of Mental Health of New Yorkers, a 2023 study published by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Health (DOHMH), New Yorkers who identify as people of color were significantly more likely to display symptoms of Serious Psychological Distress (SPD) than their white counterparts. SPD describes the negative emotional and mental experiences that can severely impact individuals’ well-being and is a key metric used by psychologists to evaluate collective mental health over time.

This disparity is largely a result of neighborhood disinvestment—the process by which resources (things like schools, housing, transportation, and park maintenance) are systematically taken away from certain neighborhoods. Over the past few decades, this process has occurred mainly in predominantly Black and Latino NYC neighborhoods and is still happening today at exceeding rates.

Desautels explains that this disinvestment has, in fact, led to a mass exodus of New York City’s Black population over the past 25 years, with families relocating to the South in hopes of better and more affordable living conditions.

“It means breaking families up, or families just kind of having to choose: ‘Do I stay near my loved ones in my community? Or do I go where I can potentially make ends meet?’” Desautels says.

As an added complication, redlining (the drawing of neighborhood boundaries based on residents’ race) has long kept Black and Brown New Yorkers in designated, undeveloped areas labeled “hazardous” or “declining” by the municipal government. Neighborhoods that were “redlined” as far back as the 1930s still have higher rates of poverty today, and 2 out of every 3 redlined neighborhoods contain predominantly residents of color.

Over the years, disinvestment and redlining have created enclaves of poverty within New York that, in turn, have led to higher rates of mental illness for those who live there. Notably, Brooklyn neighborhoods such as East New York/Brownsville, where, according to the DOHMH Study, SPD affects 11-14% of residents, also rank among the borough’s most impoverished.

Moreover, the Study reveals a stark correlation: New York City residents facing significant financial hardship, such as difficulty paying for basic needs, exhibit higher rates of SPD: 24% compared to 4% among those reporting less financial difficulty.

“People are just struggling with other issues,” says Rose Sauls, Director of BCS’s Services for People Living with Disabilities Division. “They’re struggling with food insecurity; housing is going up; homelessness is up and rising…if someone’s at home wondering how they’re going to pay their rent next month or they’re getting letters from their landlord, or they’re looking after their kids; it’s one thing after the next.”

Oftentimes, low-income individuals with mental health struggles simply do not know what resources are available to them. Even though care exists, it can be challenging to understand the complex array of paperwork and appointments needed to obtain it. Speaking to NYC’s mental healthcare system, Sauls says, “It’s not easy for a person, even someone without mental health issues to navigate.”

BCS PROS members on a field trip to Canarsie Pier

Sauls explains that the amount that one must know about Medicaid versus managed care, identification requirements, and more, often precludes people from seeking treatment at all, especially if they already feel stigmatized by their conditions.

“Especially in the African American population, they are more likely to not share or disclose that they’re going through any kind of mental health crisis,” Sauls says. “So you have a cultural piece as well, where people just really don’t want to identify themselves as having their mental health in crisis.”

At BCS PROS, a large part of Desautels’ work involves learning the city’s mental healthcare system from the inside out and using this knowledge to improve PROS members’ lives.

“It’s our job to know what some of the things are that people can get,” she says. “They may not know that they’re entitled to SSI because they have schizophrenia. They may not know that they’re entitled to an apartment in supportive housing.”

New York City has plenty of services and programs to assist people with mental illness; they are simply not widely promoted in the communities that need them most.

BCS’s programs aim to change this by educating Brooklyners about all aspects of mental health and building community between people – especially people of color – living with mental illness. This education varies from helping people come to terms with their diagnosis to assessing treatment costs to learning what forms trauma can take. Desautels states that the fundamental goal of all BCS programs is to ensure individuals are treated with compassion and dignity while also keeping programs sustainable and financially accessible.

“It’s very important that once we build this community for people – where it’s so important to their wellness – that we maintain it so it doesn’t close down,” Desautels explains.

Both Sauls and Desautels feel optimistic about the future of mental healthcare in Brooklyn. Since taking office in 2021, New York Governor Kathy Hochul has been very receptive to expanding services to people on the street who have mental health conditions by employing more clinicians and street outreach teams. Further, the city has made efforts to distinguish between psychiatric crises and criminal activity by assigning mental health professionals to individuals who would previously have been sent straight into the criminal justice system.

Sauls says that, in general, she has noticed more public officials addressing mental health in New York’s POC and low-income populations, as well as new contracts and programs being initiated. The BCS Greater Heights Clubhouse, in fact, recently had its contract renewed by the City for another nine years, and Sauls’ colleagues are now working to recruit new members through partnerships with community groups, schools, hospitals, and faith-based organizations.

BCS Clubhouse members food-prepping in the Clubhouse kitchen

“It’s definitely about letting people out in the community know, but we also have people who walk by our door and just see it says ‘wellness’ and ‘mental health’ on the sign. They come in and ask about our services, and it’s so great that we get these self-referrals,” Desautels says. “We’re rowing this boat with them so that they know, hey, there’s an island ahead, and it’s got all these tools that you can use on your journey.”

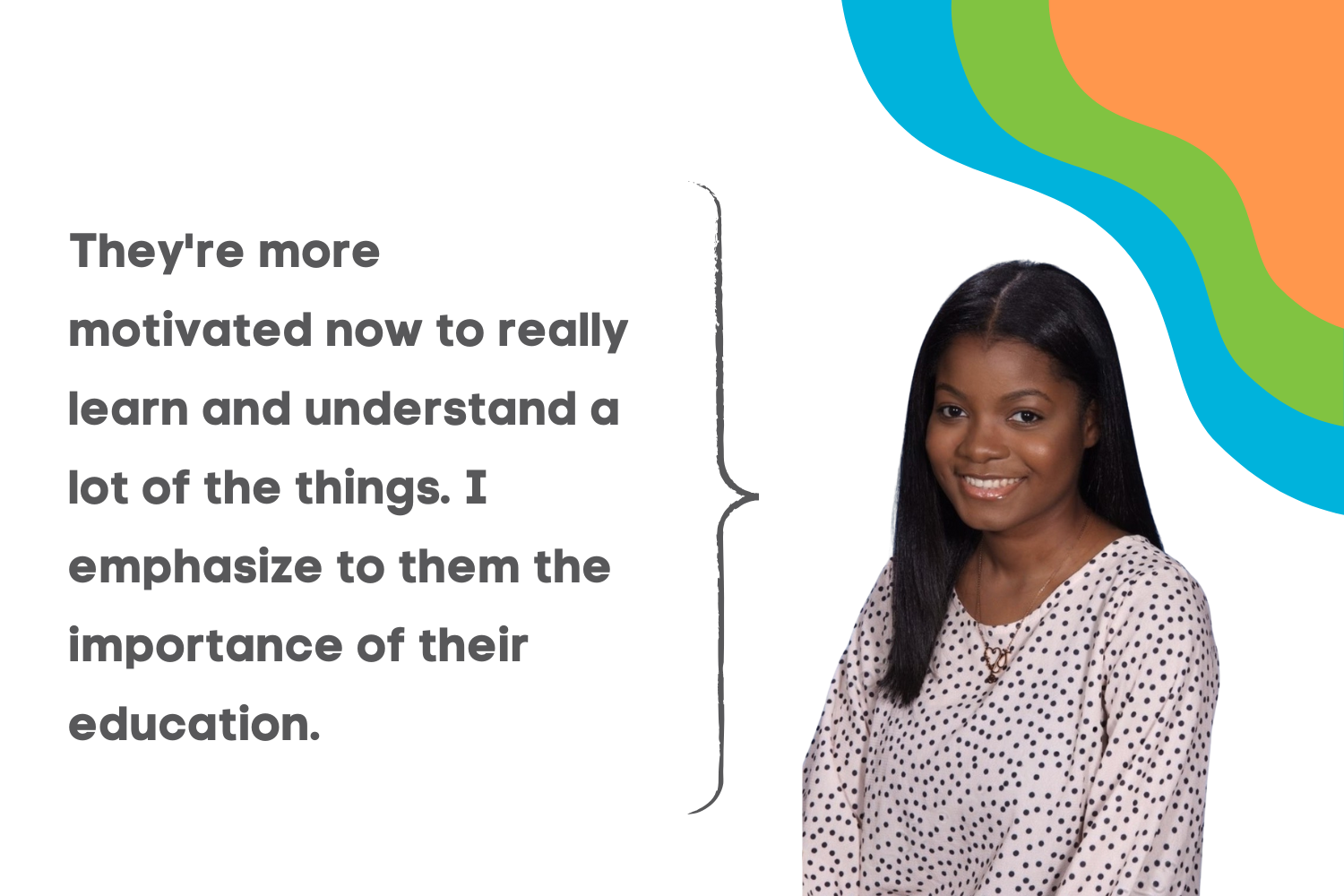

The BCS Community Health and Mindfulness Program (CHAMP).

Top Viewed Posts

Youth Art Programs

Program Spotlight: Day Habilitation

BCS Volunteers Spring into Action for Brooklyn

SUBSCRIBE

SUBSCRIBE