Invisible Barriers: Exploring the Challenges Faced by Housing Insecure Students in New York City Schools

New York City is in the midst of a housing crisis, with the Coalition for the Homeless stating that over 350,000 people are without stable housing – the highest levels since the Great Depression. Among the city’s homeless, nearly 70% of those in shelters are families, including over 48,000 children. This situation has had a major impact on the city’s public school students, with more than 100,000 students identified as homeless during the 2022-2023 school year—marking the eighth consecutive year this number has exceeded six figures.

The instability of homelessness disrupts every aspect of a child’s life, especially their education. Without a secure place to call home, these students struggle to meet basic needs, leading to chronic absenteeism, behavioral issues, and frequent school transfers. These challenges hinder their academic progress and emotional well-being, leaving them with unstable foundations for long-term success.

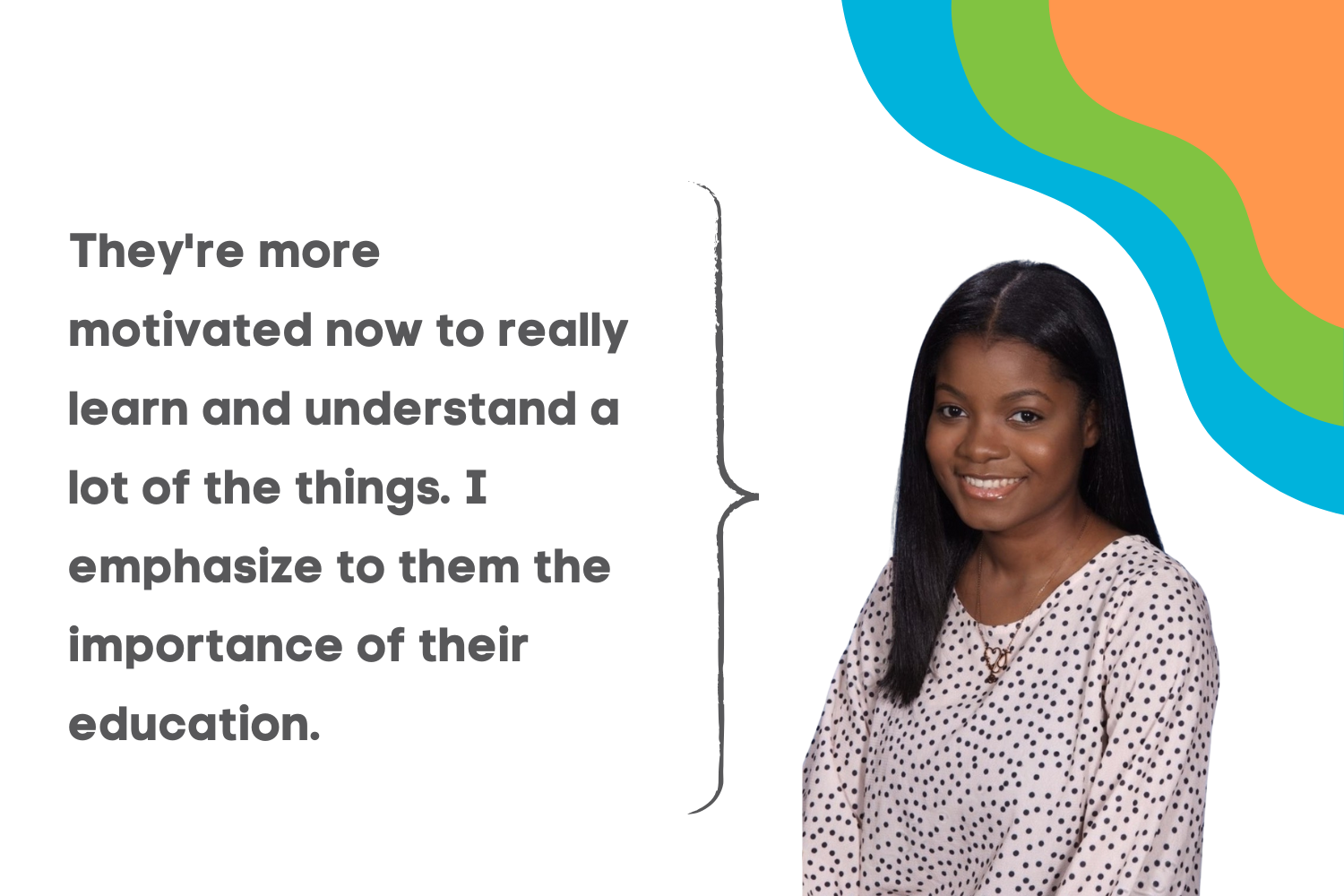

“Everyone’s three basic needs are food, shelter and clothing. When those three are compromised, it affects how you view and interact with the world,” says Hannah-Gay Lovemore, a BCS Program Director at P.S. 149 Danny Kaye in East New York. “In this context of homelessness, if I don’t know where I’m going to bed, what I’m going to experience while I’m sleeping, or if anything is compromising my living situations, it creates anxiety.”

Lovemore says that this anxiety can manifest in her students in numerous ways, from students clinging to their preferred teachers to creating glorious stories about their idealized living situations. She’s even experienced students who don’t want to leave the school building to return to their housing situations.

It’s easy for the emotional and physical stressors of housing instability to follow children into the classroom and leave them with unstable foundations for long-term academic success. A brief study by NYU Steinhardt revealed that, in 2017, over 80% of NYC students living in homeless shelters were chronically absent from school, meaning they missed about a month of the school year in total.

“I see children not show up to school because their parents don’t have it in them to support their child emotionally, and it’s just easier to keep their child home,” says Lovemore. “Or say, for example, they ran out of soap, and the parent doesn’t have perfume to mask an odor. Or maybe there was an infestation of bed bugs or roaches, and they don’t want to send their child to school with bed bug marks.”

Further, students experiencing housing instability are more prone to behavioral issues in the classroom and, thus, more likely to be disciplined–creating a detrimental feedback loop. One school social worker told NYU Steinhardt researchers, “They may become distracted and get bad grades. Or they may become unusually quiet or even act out—looking for attention and wanting to be helped by an adult.”

Christian Molieri, Program Director at BCS’s Transitional Living Community Women’s Shelter, notes that homeless youth’s behavioral issues may be the manifestation of trauma and their lack of opportunities for socialization. “They don’t have the skills or stability yet because they’re still in the fight, flight, and freeze modes. They’re just trying to survive,” Molieri says.

These social issues are compounded by the fact that homeless students switch schools more than housed students, with mid-year transfers being especially common. These changes often make it difficult for homeless students to build relationships with peers and teachers and meaningfully engage in their curriculum.

In NYU Steinhardt’s brief, a north Brooklyn public school principal nicknamed these frequent transfers “ping-pong children,” explaining that “[They’re] constantly back and forth from school to school like a ping-pong, and they’re not getting that stable education. When you get a child who has been in three or four different schools, and they’re eight years old, it’s difficult to adequately educate [them]…because you’re constantly playing catch-up.” According to estimates by the U.S. Department of Education, every mid-year school transfer sets a student back academically up to six months, meaning that kids who transfer multiple times could struggle to catch up to their peers years into the future.

Fortunately, in recent years, NYC has made it easier for homeless people outside of the city’s shelter system to access aid. Additionally, the city government has accelerated the delivery of 15,000 supportive housing units and made efforts to reform zoning laws and preserve existing below-market-rate homes. The city’s primary homelessness-prevention program, Homebase, also provides services for families at risk of homelessness, including legal assistance, help obtaining public benefits, emergency rental aid, and financial counseling.

To Molieri, it’s important to remember that NYC’s homelessness crisis will not be solved overnight. “We can’t get overwhelmed by the large, huge homeless epidemic,” they say. “We have to start with small steps and have strategies to approach. With those steps, and then breaking down those steps further, we can navigate to rebuild these systems.”

While numerous programs exist to keep NYC families stably housed–the nation’s largest public housing authority, rent vouchers, childcare subsidies, etc.–there’s still significant work to be done on an interpersonal level.

As Molieri explains, BCS addresses housing insecurity with a smaller-scale, more individualized approach. “It’s important to go to that individual from the start, and, just as an introduction, say, ‘Tell me about yourself. Who are you? Welcome, and thank you for staying here’ while also being realistic that we are working as a team. We can’t do it all for someone, just as they can’t do it alone.”

BCS’s Education and Youth Development Division provides programs for Brooklyn students across the socioeconomic spectrum, ensuring that all children have opportunities to succeed in future academic and social endeavors. Staff in these programs must meet each child where they are and understand how their circumstances may impact their ability to engage in school.

Students at PS 149 Danny Kaye

Some classroom conversations about home life may be triggering for students experiencing homelessness; for example, teachers asking students what they ate for breakfast or what they did when they went home the day before could bring up unpleasant feelings for students in unstable environments.

Lovemore explains that at PS 149, teachers are trained to use open language that will not make homeless students feel othered or inferior to their peers. “When a teacher asks, ‘Well, what did you do when you left school?’ That leaves it open,” Lovemore says. “As a student, I’m not obligated to say, ‘Well, I did my bath time routine,’ because I might not want to explain that my bath time routine was at a kitchen sink and not in a bathtub.”

This September, teachers at PS 149 will take a trauma-informed training course that will show them how to match their language to each student’s needs and help students release their emotions in a healthy and safe space. “If the staff know how to regulate their emotions and manage their feelings, then they can recreate that space for the children,” says Lovemore.

PS 149 also promotes an open-door policy with parents, thus fostering an environment where parents do not feel shame or embarrassment about revealing their hardships to faculty and staff. Lovemore hopes to deepen ties with families by starting workshops and classes that parents can participate in on topics like resume writing and job applications. The goal, she explains, is for parents to see BCS as an additive resource: not only an after-school program for their children but a space where they, too, are supported.

New York City’s homelessness issue will not be solved quickly or easily, but Lovemore feels confident about BCS’s role in making things easier for affected Brooklyn families. “My role as Program Director is not solely to help the children,” she says. “Their parents have to feel safe and supported, and it is important to do my part in ensuring that the parents know they can always come to me.”

Top Viewed Posts

Youth Art Programs

Program Spotlight: Day Habilitation

BCS Volunteers Spring into Action for Brooklyn

SUBSCRIBE

SUBSCRIBE